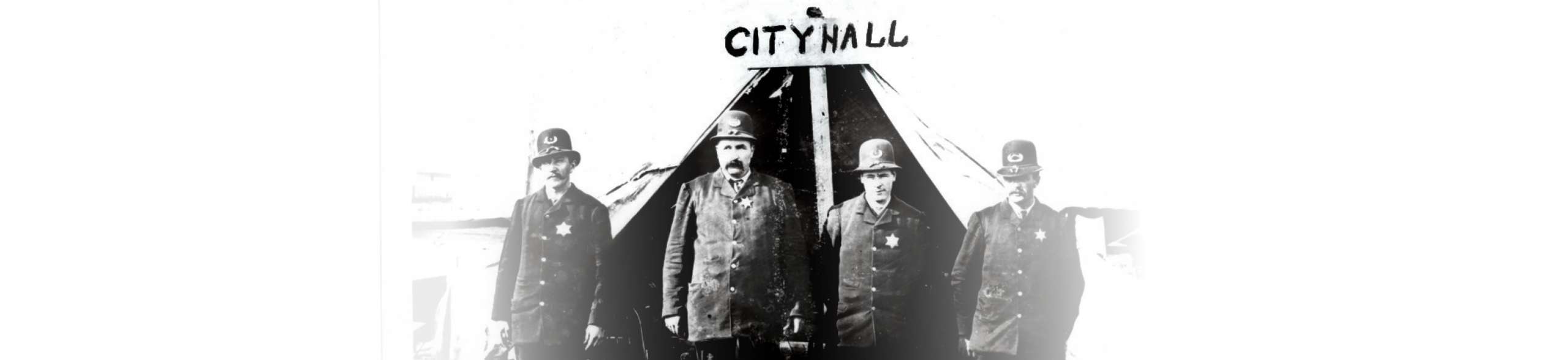

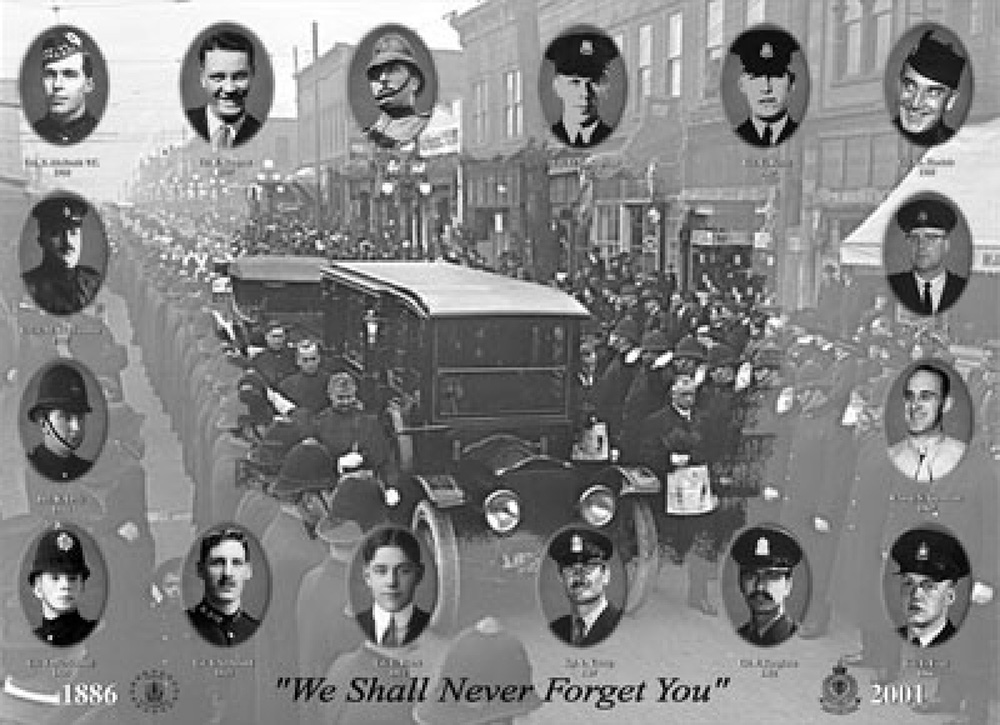

The Vancouver Police Department has been in existence since 1886. Since that time, 16 officers have been killed in the line of duty. They were husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons, and their sacrifice will not be forgotten.

Constable Lewis Byers

In November of 1911, and despite his young 20 years of age, Constable Lewis Byers came to the Vancouver Police Department. He had worked for both the Winnipeg Police and the North West Mounted Police (NWMP). When the NWMP required him to ask permission to marry, and then denied his request, Constable Byers quit and married Annie Woodcock. After the couple lost their month-old baby, he brought his bride back to her home town of Vancouver.

Tragically, just five months later, Constable Lewis Byers would become the first Vancouver Police constable killed in the line of duty – and to this day, the youngest.

On March 25, 1912, a drunk and belligerent customer entered the liquor store on Powell Street near Hawks Avenue. When staff refused to serve him, he became angry, threatening them, and waving his .38 revolver to emphasize his point. The man walked out, back to his waterfront shack a few blocks away.

Store staff phoned the police, and Constable Byers arrived to get information about the suspect. Witnesses could only provide an approximate address – a shack on the eastern side of Hawks Avenue, near the Great Northern Railway wharf and the BC Wire and Nail Company factory.

Constable Byers approached the area, trying to determine which of the numerous shacks belonged to the suspect. Suddenly, five yards away, the door of a shack flew open and the suspect stood in the doorway. He pointed his revolver at the constable, forbidding him to take another step.

Constable Byers ran for cover and he drew his revolver. The suspect fired three shots, two of which hit the officer – one in the chest and one in the neck. He died immediately.

Detective Crewe and Constable Barker came to the ambulance call on the wharf, at the foot of Hawkes Avenue. As they approached, they could see Constable Byers lying on his side, with a bullet wound in his chest. He was about four yards east of the suspect’s shack, who continued to fire his weapon.

Detective Crewe managed to drag Constable Byers out of range of the gunfire and into an ambulance. Sadly, a bullet had hit his heart, and he died on the way to the hospital. Crewe requested back-up and Detective Champion, Sergeant Munroe, and Constable Quirk answered. The officers riddled the shack with bullets, as the suspect inside kept firing. When the shots ceased, Constable Quirk cautiously opened the door. The assailant was lying on his side, shot in the chest and neck. Inside, the officers also found the revolver and a box of .38 calibre cartridges.

Constable Russell, who had just arrived via streetcar, got a stretcher and took the suspect to the General Hospital. He was unconscious, but alive. Doctors found five bullets in his left breast – apparently, self-inflicted – and two wounds on the right temple, one of which would be fatal. He only survived another 30 minutes.

Except from the Vancouver World newspaper, April 1st 1912, reprinted with permission:

Sorrowing Thousands View Somber Pageant

It was evident on all sides that the crowd manifested a genuine sorrow, intermingled with admiration of the heroic constable who had fallen a martyr to the bullet of an assassin in the performance of his duty, But during the passing of that great pageant the hearts of the crowd were deeply touched with sincerest sympathy at the spectacle of the lonely figure of the young wife who passed by, weeping bitterly in a carriage, behind the hearse. Those few in the crowd who were able to obtain admittance into the church could not fail to notice, seated in the front pew in front of the casket containing the body of her husband, the sad drooping figure of Mrs. Byers who had been deprived of the gallant husband who had laid down his life in the execution of what is at all times a perilous duty.

Lewis Byers: police officer, husband, son.

Addendum

Five years later, in 1917, Constable Russell was wounded in the face during a shoot-out with the suspect who murdered Constable MacLennan.

Constable Quirk was shot and wounded in the hand ten years later, in 1922, trying to arrest the suspect who murdered Constable McBeath.

More information

British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial

This week in history: Historic revolver donated to Police Museum

by John Mackie

Vancouver Sun

June 27, 2014

Fallen Vancouver police officer honoured in Carievale

by Brady Bateman

Estevan Mercury

September 27, 2018

Lewis Byers

Constable James Archibald

On the night of May 28, 1913, Constable James Archibald headed out to walk the beat on Powell Street. When he failed to return to the station after his shift, a search was launched. His fellow officers found his body in a vacant lot on Powell Street the next morning. He had been shot three times.

Constable Archibald spent his last shift diligently patrolling the commercial area on Powell Street, as there had been a recent rash of burglaries. The investigation into his murder would later reveal that as he was walking past the office of Hastings Shingle Mall No.2 in the 1300 block of Powell Street at 1:30 a.m., two men were coming out a side door after burglarizing the business. When one of the men lit a cigarette, Constable Archibald saw the flash from the match, and walked toward it.

He approached cautiously, holding his flashlight in his left hand and his revolver in his right. When his flashlight captured the two men, he asked them what they were doing. One of the men told him they were looking for a place to sleep in the bushes. The constable was suspicious and detained them for further investigation. In order to search them properly, he needed both hands, so he put his revolver back in his holster. When searching the first man, later identified as Herman Clark, he quickly found a pry-bar hidden in his pocket. At this point, he would have realized he was in a dangerous situation – outnumbered by two burglary suspects.

Constable Archibald reached for his revolver to arrest them, however Clark and his partner-in-crime, Frank Davis, were both also armed. Clark drew first, shooting the constable three times from point blank range, killing him instantly. The men fled, but then quickly returned to hide the evidence. They hid Constable Archibald’s body in some nearby bushes, and tossed his revolver and flashlight, along with their burglary tools, into a mud-hole.

The two men, however, left behind valuable evidence next to the body – a crudely-made, black cloth mask, which would lead to their arrest later the same day. Detectives Levis and Tisdale made the arrests, arresting not only Clark and Davis, but also Joseph “Blackie” Seymour and William Hamilton. An informant’s tip led police to their hideout in a nearby waterfront shack. When searched, police found a match to the mask found beside Constable Archibald’s body. A piece of black material was found with the outline of the mask cut from it.

All four men were taken to jail and interrogated by Detectives Levis and Tisdale. As they were all facing the death penalty, Joseph “Blackie” Seymour and William Hamilton quickly decided to give “King’s evidence” and were granted immunity.

They provided evidence to the investigators regarding where the murder weapon was hidden and also testified at the trial. On November 6, 1913, Clark and Davis were found guilty. His lordship Justice Morrison sentenced them “to be hanged by the neck until dead.”

They were hanged on May 15, 1914, in the provincial jail in New Westminster almost a year after the murder.

Constable James Archibald was 27 years old when he died, with only 13 months on the job with the VPD.

Addendum

During the investigation, a background check of Clark revealed he had escaped from Folsom Prison in California on July 29, 1912, where he was serving a 12-year sentence for first-degree burglary.

Ironically, Detective Levis, one of the arresting officers, would also be killed in the line of duty almost a year later.

James Archibald: police officer, husband, father, son.

Poem

The following is a poem, published in the Vancouver Daily Province on May 28, 1913, author unknown.

James Archibald – Hero, Vancouver Police Force

Don’t think that our heroes are all of the past, That they live but in song and in story,

As long as the name of “A Briton” shall last,

Our sons will win honor and glory,

And not only then0when the “war-drum” may beat –

Do some merit Victoria’s Cross –

In this city of peace stay the din of the street,

While we mourn a brave hero – our loss,

A wreath for “James Archibald – Hero of Peace”

Who answered when “Duty” did call –

For a moment the tumult of Vancouver cease –

As in silence we follow his pall.

Then! – a cheer for our policemen – their children and wives,

Of such men our Vancouver is proud.

When “Duty” doth need it, they’ll give up their lives

For the careless and confident crowd.

“For the crowd” – who are careless and rugged and cold,

(We’re not great on “Emotions” out West.)

But we know the right color and valor-and gold,

We can value “What comes thro the test.”

Then a wreath for a hero who gave up his life,

Who answered when “Duty” did call,

And remember, my brothers, his children and wife

Have a claim on us, boys-one and all.

James Archibald

Constable John McMenomy

Constable John McMenomy was assigned to the “B” sub-station in Kitsilano when, on November 1, 1913, he was called to W.8th Avenue and Cypress Street for an emergency. A short circuit was causing an arc-style streetlamp to sputter and the “cut-out” box to flame.

The constable stood beneath the light and took hold of a rope used to raise and lower the arc lamp. He then gently shook the rope, believing this would seat the lamp and stop the short circuit. Instead, the street light went out, along with all the other street lights on the block.

Sensing danger, Constable McMenomy immediately let go of the rope and warned two small boys to move away, as they were standing nearby watching. He then returned to the pole to attempt to turn the lights back on. The constable began to reach for the same rope, not realizing a live electrical wire had broken off the top of the pole, and was now beside him about four feet from the ground.

The black wire was almost invisible in the darkness, and as Constable McMenomy continued reaching for the rope, the metal buttons on his tunic met with the wire. He was electrocuted, and collapsed to the ground.

Constable McMenomy died in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. He was 22 years old. A former Dominion Police of Canada officer, he was with the VPD for only ten short months.

John McMenomy: police officer, husband, father, son.

More information

2012 VPD Annual Report

VPD Officer Honours a Fallen Member

British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial

John McMenomy

Detective Richard Levis

Vancouver Police Detective Richard Levis and his partner, Detective Malcolm McLeod, were investigating a stabbing on the evening of August 27, 1914. A dispute had taken place in a local café, and the suspect, T.T. McKillarney, had stabbed a man named Thomas Hoggan.

Just before 11:00 p.m., the two detectives went to McKillarney’s shack at 732 Alexander Street. Detective McLeod covered the lane to prevent an escape, while Detective Levis knocked on the front door. The woman who answered the door stated that McKillarney was not there.

Levis suspected she was lying and decided to search the shack. He cautiously approached the bedroom, armed with his revolver in his right hand and a flashlight in his left. As he opened the bedroom door, McKillarney was waiting in ambush with a sawed-off shotgun. Detective Levis was shot point-blank in the chest.

Hearing the shot, Detective McLeod ran into the shack. Levis fell into his arms and exclaimed, “He shot me. He never gave me a chance.” He died in hospital two days later at the age of 28.

McKillarney escaped and fled to his native United States. A few months later, he was arrested while hiding out in Chicago, and he was returned to Vancouver to stand trial. He was convicted based on the testimony of a material witness named Byron Martin – a morphine and cocaine addict who has sawed off the shotgun for him. McKillarney was sentenced to death and hanged.

Detective Levis was a Vancouver Police officer for four years and, ironically, had arrested the killers of Constable James Archibald just one year before.

Detective Levis was awarded the Vancouver Police Medal of Valour posthumously by the Police Commission, which was accepted by his widow. She later joined the Vancouver Police Department as a matron and served for many years.

Richard Levis: police officer, husband, father, son.

More information

Richard Levis

Chief Constable Malcolm MacLennan

There were 250 people working in the Vancouver Police Department in 1917, policing a city of 100,000 people. They were led by Chief Constable Malcolm MacLennan, who was very popular with his officers and with the citizens of Vancouver.

One of MacLennan’s first acts as Chief was to improve the working conditions in the Department. At the time, officers worked seven days a week, with no days off. At his insistence, they were granted two days off per month. As well, he negotiated with the Police Commission to get his officers a pay raise. He was the first Vancouver Police Chief to hire a visible minority, Constable Raiichi Shirokawa, a Japanese Canadian hired in 1917. Sadly, he only served for a few months before pressure from the Japanese community forced him to resign – they believed he was being used to spy on them. Chief MacLennan was also an advocate for the growing drug addict population, lobbying politicians for a treatment centre to provide medical care for addicts, rather than treat them as criminals. His pleas fell on deaf ears.

On March 20th, 1917, Chief MacLennan was called away from his ten-year-old son’s birthday party, when a landlord / tenant dispute resulted in gunfire, wounding the landlord, a police officer who responded, and eight-year-old George Robb.

The incident began when the landlord tried to collect four months of back rent from an American named Robert Tait, who lived with his girlfriend in an apartment above a grocery store at 522 Georgia Street. The tenants were both morphine and cocaine addicts. Tait came to the door brandishing a shotgun, and threatening the landlord by saying that he would “blow his brains out.” The landlord, Frank King, called the police, and Detective Ernest Russell, and Constables John Cameron and Duncan Johnstone were the first to arrive.

The officers joined the landlord as he knocked on Tait’s door to try to talk to him. Tait responded by shooting his shotgun at them through the glass window in the door, showering them all with glass, splinters, and buckshot. Detective Cameron and Frank King were each permanently blinded in one eye. Detective Russell was also wounded in the face, but was able to function. They all retreated to the street and flagged a passing vehicle to take the wounded to the hospital. Detective Russell went to a nearby police call box to call for reinforcements.

Tait began recklessly firing a rifle from his window onto E. Georgia Street, shooting eight-year-old George Robb, who was walking from his house at 548 E. Georgia to the store beneath Tait’s apartment to buy candy. Tragically, he died an hour later in hospital.

Police reinforcements arrived and surrounded the building and a stand-off ensued. When Chief MacLennan arrived at the scene, he tried to negotiate with Tait and convince him to surrender, but to no avail.

The Chief decided they would storm the apartment. He never sent a man where he would not go himself, so he took the lead, armed with only a heavy fire axe to chop through the door.

Tait had barricaded himself in his bedroom at the back of the apartment, armed with two rifles, two revolvers, and a shotgun – easily out-gunning the police. A fierce gunfight ensued as the officers entered in the dark. They emptied their revolvers, but were forced to retreat a second time to re-load. Once outside, they discovered the Chief was not among them. Tragically, he lay mortally wounded inside the apartment.

The intense gunfire prevented his rescue. Normally, they would have ended a stand-off by dynamiting the house to flush out the suspect, but they did not know if the Chief was still alive or not. Police sharpshooters kept the suspect pinned down over the next four hours, while several unsuccessful attempts were made to rescue the Chief. Gradually, Tait’s return fire diminished as he ran out of ammunition.

A last attempt to retrieve the Chief was successful. They found him dead from a gunshot to the head, which had likely killed him instantly. As officers prepared to smoke the suspect out with sulphur pots, they heard a single shot ring out, followed by quiet. Twenty minutes later, Tait’s girlfriend, Frankie Russell, finally surrendered to police after they threatened to dynamite the house. Inside, Tait lay dead on the floor, having committed suicide by shooting himself in the head with his shotgun.

Malcolm MacLennan: police officer, husband, son.

More information

Dictionary of Canadian Biography – Greg Marquis

The murder of Chief Malcolm MacLennan and nine-year-old George Robb

by Eve Lazarus

Every Place Has a Story

What Frankie Said

by Lani Russwurm

Past Tense Vancouver Histories

Shoot Out on the 500 block of East Georgia, March 20, 1917

by James Johnstone

When an Old House Whispers

British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial

Malcolm MacLennan

Constable Robert McBeath V.C.

It was 2:30 in the morning of October 9, 1922. Constable Robert McBeath and his partner, Detective R. Quirk were walking the beat downtown on Granville at Davie, when they noticed an erratic driver.

The driver was honking and the car moved from side to side as it headed north on Granville. Constable McBeath stepped into the road and signalled for the driver to stop. When he refused, both officers jumped on the car’s running boards.

The car finally came to a stop, and McBeath escorted the driver, Fred Deal, to the patrol box, while Quirk remained with Marjorie Earl, the passenger. A loud noise alerted Quirk to McBeath’s struggle with the driver.

Detective Quirk saw the flash of a gun as he ran to help, and saw that the gun was pointed at him. When he swatted it aside, he was shot in the hand. Deal fired the gun again, hitting Quirk on the side of the head as they struggled. He fell to the ground, hearing a third shot, and Constable McBeath fell on top of him. The detective moved out from underneath McBeath and Deal fired again as he tried to make his escape. The bullet went through Detective Quirk’s coat.

Quirk rolled McBeath onto his back and fired at Deal. More shots were exchanged as he attempted to follow the shooter. His injuries prevented him from keeping up.

Both officers were rushed to St. Paul’s Hospital. McBeath died shortly after they arrived. He was 24-years-old.

Officers showing a photograph of Deal around the area were able to find out where he was hiding out. Constable Langham arrested him shortly after. He was unarmed, but an area search located the murder weapon on the landing of a billboard at Drake and Granville where it had been thrown.

Deal was charged with the murder of Constable McBeath and the attempted murder of Detective Quirk. Once convicted, he was sentenced to hang on January 26th, 1923, however, the conviction was overturned on appeal and a new trial was ordered. This time Deal was convicted of manslaughter by judge and jury, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment. He served 16 years in prison in Canada and then was deported in 1938 to a prison near his former home in Florida for the rest of his term.

Only seven years earlier, Robert McBeath was a sixteen-year-old boy living in Kinlochbervie, Scotland, with his adopted parents, Robert MacKenzie and his sister Mrs. Barbara MacIntosh. World War One had been raging for a year, and McBeath was eager to fight. He told the recruiters he was 18 and joined the Seaforth Highlanders Regiment in Scotland.

On November 20, 1917, he was a two-year war veteran, fighting with his unit in the battle of the Somme in Cambrai, France. The Seaforths took part in the first battle ever carried out with massed tanks and easily broke through German lines. The Germans counterattacked the next day and recovered all the ground they had lost. The Seaforths were pinned down by intense gunfire from several machine gun nests and suffered heavy casualties.

Lance-Corporal McBeath volunteered to attack the guns alone, armed only with a Lewis gun and revolver. He stormed the first machine gun nest, killing all the enemy soldiers. He was joined by a tank, and then attacked the other four machine gun nests in succession, silencing them as well. The remaining enemy soldiers, fearing they were under attack by a larger force, retreated from their trench into the shelter of a tunnel. The Highlander’s warrior blood was hot, as he fearlessly pursued them into the tunnel and shot the first one dead who tried to fight; the remaining three officers and thirty soldiers surrendered to him.

As a result of his heroic action, he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Prior to the Seaforths going overseas, they were reviewed by the Duke of Sutherland. The Duke promised “croft land” to every man who returned, and a farm to whoever won the Victoria Cross. When Robert McBeath returned home to Sutherland he was given a hero’s welcome. The people of Sutherland treated him like a lord and presented him with a silver tea service. He renewed his love affair with Barbara MacKay, the daughter of John and Williamina Morrison MacKay. They were married in Edinburgh on February 19, 1918.

Robert was awarded a farm as promised by the duke, but it was not for him. Seeking more adventure, he sold the farm and emigrated with Barbara to Vancouver. He joined the British Columbia Provincial Police, and then several months later, the Vancouver Police Department. After his death, Barbara was homesick and moved back to Scotland. She remarried and died childless in her mid-40s as Mrs. Alec MacDonald. She is buried in Scourie, Sutherlandshire.

Constable McBeath’s funeral was one of the largest ever in Vancouver history. All stores and banks were closed. Thousands of people attended to give their respect. The funeral procession took 20 minutes to pass by the main post office. It was led by Vancouver Police Inspector George Hood on horseback and two other mounted policemen, followed by the Vancouver Police Pipe Band, then the widow Barbara in a hearse. Next was the mayor and council members, followed by 300 Masons marching four abreast, and behind them were 80 hand-picked members of the Vancouver Police Department led by Chief Constable James Anderson. The rest of the procession included 100 members of the Vancouver Fire Department came next, 12 members of the Royal Canadian Mounted police in scarlet uniform, 50 members of the Seaforth Highlanders Regiment Vancouver, a contingent from the Irish Fusiliers of Canada, and several hundred World War One veterans. As well, there were 40 members of the BC Electric Railway, 12 members of the Canadian Pacific Police, several hundred members of the Foresters, St. Andrews, and Caledonia Societies. Bringing up the rear were several hundred members of the public. As the procession passed by, heads were bared and a reverent silence befell the crowd.

At the church service, Reverend J.S. Henderson eulogized him as follows:

“Probably not since the murder of Chief MacLennan has an event so stirred the entire community with profound sorrow as the tragic event of Monday morning when in the discharge of his duty, on one of our public streets, the life of this brave young officer was taken. Many did not know him by sight, could not call him by name, but there were few hearts in homes that were not sad when the news of the event became known.”

He then described how he won the Victoria Cross:

“Upon that splendid record I need not dwell, it will find a place in the annals of the Empires deathless dead. But I would that in the solemn atmosphere of this hour we might catch a vision of his great noble spirit, the high purpose and devotion and enthusiasm with which he gave himself to his life’s mission. Canada’s greatest need is just such men. This brave young officer will not have died in vain if his tragic passing will awaken a new civic spirit in relation to our police force. A new purpose on the part of the authorities to rid this city of that herd of undesirables, who through someone’s blunder has made Vancouver it’s breeding and feeding ground.”

Thousands of people viewed the open casket at the Vancouver Police station. The entrance hall was filled with floral tributes, with two Union Jacks forming a background for the grey casket, which was draped with another Union Jack. A wreath in the form of a Victoria Cross lay at the foot of the coffin and the Masonic Insignia was placed upon it.

Chief Constable James Anderson was quoted as saying,

“Orders went out last night for a thorough clean-up of the city. We have been doing the best we can with the small force at our command, but special precautions will be taken from now on to check all people carrying firearms and all cases of immorality and drug dealing. A high-speed car with three men armed with guns in an essential part of the police equipment of any large city. In Vancouver it is all a question of getting enough money.”

The Victoria Cross is the highest medal awarded for bravery in the British and Commonwealth armed forces. The medals are made from bronze, melted down from two Russian cannons captured by the British Army in the Crimean War, during the charge of the famous “Light Brigade” in 1854. The chance of surviving a Victoria Cross act is 1 in 10.

The Vancouver Police Department christened a police boat the “McBeath” to honour his death.

Mount McBeath, in Jasper National Park in Alberta, is also named in his honour.

Robert McBeath, V.C.: police officer, Highlander, husband, son.

More information

British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial

Christening of the R.G. McBeath

Cairn Dedication for Fallen Vancouver Police Officer

Kinlochbervie’s memorial to Robert McBeath VC

Lyrics for Robbie McBeath by Tiller’s Folly

‘Conduct beyond praise’: the story of Sutherland’s only WW1 VC winner

The Press and Journal

July 8, 2021

Robbie McBeath by Tiller’s Folly

Robert McBeath V.C.

Constable Ernest Sargent

It was November 5, 1927, and Constable Ernest Sargent was walking a one-man beat on the west side of Vancouver.

He stopped in the 2700 block of Alder Street at 4:30 a.m. to make a mandatory hourly call to his dispatcher, reporting that everything was fine.

As he hung up, he noticed a suspicious man across the street walking toward him. He walked toward him, and asked him what he was doing out so late. The Chinese man, who appeared to be about 40 years old, mumbled a reply and continued walking past Constable Sargent.

Suddenly, the man drew a .38 calibre semi-automatic pistol and shot the constable in the stomach at point blank range. He fired a second shot, but missed. Despite being wounded, Constable Sargent managed to draw his service revolver and fire all six shots at the suspect as he ran away. He staggered across the street back to the police call box and phoned for help.

A neighbor, who happened to be a doctor, heard the shots and came out to investigate. He helped the wounded officer into his house and administered first aid until the ambulance arrived.

While in hospital, Constable Sargent managed to give a detailed description of the suspect and picked him out of a mug-shot book. He was identified as Leong Chung, a well-known criminal, and a warrant was issued for his arrest.

Crime scene investigators found evidence of an attempted break-in to a home at 2720 Alder Street the same day as the shooting. There were footprints in the soft dirt underneath a basement window and a small woodpile was knocked over. It appeared Chung had been planning the break-in when something disturbed him.

Surgeons operated on Constable Sargent, but they were unable to stop the bleeding. He died five days later on November 10 at age 25, after only three years on the job.

Chung was arrested several days later in Victoria. He faced trial, but was found not guilty.

The case remains unsolved.

Ernest Sargent: police officer, husband, brother, son.

More information

Ernest Sargent

Constable Joseph Reilly

As senior officers, Constables Joseph Reilly and W. Oliver had the privilege of driving a brand new “police radio” car, rather than walking the beat.

It was just after midnight on November 27, 1932, as the partners drove south through the intersection of Burrard and W. Georgia Street, when they were suddenly struck by another vehicle.

Constable Reilly was thrown from the patrol car, and suffered a skull fracture and two broken legs. He never regained consciousness, and died one month later on December 23 at Vancouver General Hospital.

Constable Joseph Reilly was born on September 9, 1878, on Prince Edward Island. He joined the Vancouver Police Department on August 25, 1914, at 36 years of age. His service record indicates he was hired as a “temporary fourth class constable to take place of a constable at war.” When he was hired as a regular constable on June 4, 1915, he was paid $960 per year.

Joseph Reilly: police officer, husband, father, son.

More information

Joseph Reilly

Constable Charles Boyes

Constables Charles Boyes and Oliver Ledingham were shot and killed by three bank robbery suspects, and Detective Percy Hoare, was shot and wounded.

The following story is reprinted with permission of the Vancouver Sun newspaper, originally published on February 26, 1997, written by Lindsay Kines:

Percy Alan Hoare returned to the scene of the crime 50 years later and saw nothing he remembered. A Skytrain now skirted the railyard near Clark and Great Northern Way, a new Home Depot store sprawled next to the tracks and someone had even paved the side roads. The 90-year-old former police detective surveyed the site of one of the most horrific gun battles in Vancouver Police history and found nothing familiar. “It’s all changed,” he said. All except for the grass and brambles still choking the ditches near the tracks – Hoare remembered them too well. Fifty years ago today, the Vancouver Police detective fell there, two bullets in his leg and shoulder, two fellow officers dying nearby and a would-be bank robber lying dead a few metres away. The shooting stunned a city just two years out of the Second World War, scarred a police department and, like so many murders before and since, wounded more people than were shot that sunny afternoon.

If anyone doubts the damage done by a few seconds of violence, the shooting on False Creek Flats might convince them otherwise. It left a senior police detective haunted by nightmares and a boy without his father.

It led to the death of a fourth man by capital punishment, forever altered the life of a six-year-old girl and remains so painful for some family members that 50 years after that day, they still don’t want to talk about it. “People just don’t know what you go through,” Naomi Macey said in a telephone interview this week from her home in Calgary. Half a century ago, she lost her father in the gunfight. The memories of that day and its aftermath still catch in her throat. “It had,” she said, a “horrendous impact on our family.”

The events of Wednesday, February 26, 1947, began routinely with an anonymous call to police headquarters just before noon. The caller told a detective that men were putting on masks in a car near First and Renfrew, apparently preparing to rob the Royal Bank. The detective dispatched plainclothes officers to the scene, and the sudden police attention apparently spooked the would-be robbers. They took off in a maroon car, which they later abandoned in front of a house at 2325 Kitchener. Hoare and his partner, George Kitson, found the car a short time later. While Kitson stayed with the stolen auto, Hoare went in search of the bandits. He soon spotted 12-year-old Arnold Montgomery near Lord Nelson School. The boy said he had seen the three men, and Hoare took him in the police cruiser to help hunt for the trio.

They headed west and saw the suspects walking along the railway tracks near the Great Northern Roundhouse. Arriving only minutes after officers Charles Boyes and George Ledingham, Hoare parked the car, showed Montgomery how to work the radio and ran to help. Hoare later testified that he saw Ledingham flash his badge and step in front of the three men – subsequently identified as Harry Medos, 23, Douglas Carter, 18, and William Henderson, 17. “They spread out in a line, coming toward me on the tracks,” Hoare testified. “And when I was about 10 feet away, I asked: ‘Who are you three fellows anyway?'” There was no reply. Then the wind blew open Henderson’s coat and Hoare spotted the butt of a handgun sticking out of his pants. The detective reached down, pulled out the gun and asked: “What are you doing with that?” Before he could say anything else, all hell broke lose.

Running along the tracks, Medos and Carter wheeled and fired on the officers, killing Boyes, 39, and Ledingham, 40, and wounding Hoare in the hip. “I tried to get my gun out as I fell,” Hoare said later. “As I did this, a bullet hit me in the left shoulder.” He lay quiet for five seconds, feigning death. Then, still prone and bleeding, he shot the running Carter and saw him fall in the weeds. Medos and Henderson headed in another direction and Hoare, who had learned to shoot on a farm in Alberta, fired a long, arching bullet that hit Medos in the buttocks. By then, Carter was back on his feet and Hoare, still on the ground, fired again. This time, Carter fell and did not get up. “I could hear him breathing from where I sat,” Hoare told a coroner’s jury. “He must have expired a short time later.”

Montgomery, who watched the shooting from the police car, radioed for help, then ran to Hoare’s side. Now retired from his job at B.C. Electric and living in Parksville, Montgomery, 62, said he has kept his role on that fateful day to himself. “I never told anybody, hardly,” he said. “Just a few close friends. I just didn’t want to talk about it, that’s all. It’s something that’s in the past and it’s not important anymore.”

Roy Tabbutt arrived at the scene a few moments after the shooting just as Boyes was closing his eyes. The two men were partners for two or three years until both got promoted to plainclothes duty earlier that year. The friends saw each other for the last time only minutes before the shooting. Tabbutt was headed in one direction searching for the suspects and Boyes in another, but for some reason, they swapped routes, Tabbut said. “The next time I saw him, he was dead.” Now 84 and long since retired from the police department, Tabbutt has often wondered over the years what might have happened if he and Boyes had not changed routes. He has never forgotten that day. “I guess it’s one of those things, you know, that happen when you work like that,” he said.

Police found Medos and Henderson holed up in a basement at 647 East Sixth, and seven months later, Medos was hanged for the murder of Boyes. Henderson was convicted, but acquitted on appeal. He subsequently served time for heroin possession, and his whereabouts today are not known.

Police estimated that 100,000 people stood 10-deep along Burrard and Georgia streets for the funeral of the two dead officers. Naomi Boyes, who was just six years old at the time, did not attend the funeral, perhaps because she was considered too young. She was not, however, too young to absorb the pain. “I remember being told and then everything kind of went blank.” Now a mother of two boys, Naomi Macey, 56, spent four years in therapy in later life to work through that time. “I kind of lived in my own little world, but I think I’m sort of coming out of that now,” she said. “Things are seeming to be a lot better, but it did take a long time.” She remembers her father performing magic tricks, which he had learned from the Fakirs in India, where he served in the British Army. She remembers, too, her father inviting other policemen over in the evening to play poker. She would sneak from her bed and creep up on to his knee to watch them all play. Fifty years after his death, certain events still trigger the emotions of that time. “I guess the only other thing I can say about it is every time a policeman dies on duty, it’s like an intense blow to the solar plexus for everyone in my family,” she said. “I went to a bank in Calgary close to where I work last spring and I arrived about 15 minutes after it had been robbed and my stomach did flip-flops just looking at the scene.” Her mother, who remarried, has said not a day goes by that she doesn’t remember that time. “It seems that these kind of intense incidents in life imprint themselves on us on a cellular level,” Naomi Macey said. “And so every time something comes up to remind us of this, all the emotions come right to the surface again.”

Bill Ledingham, who was 13 when his father died, prefers not to talk about that time now. A retired schoolteacher, he said he remembers little of it, except that he had to work summers after his father’s death to earn extra money. “I liked those days,” he said. “I learned a lot about life digging ditches.” But he sees no value in dredging up the unpleasant past – the anniversary stories only upset his mother and serve no real purpose.

Retired Vancouver Police Inspector Ian Sinclair – whose own father, Gordon, was killed on the job in 1955 – said he understands Ledingham’s reluctance. Sinclair said his own mother and sisters suffer every time something is written about their dad. He also said there is value in remembering the risks of the job and the sacrifices officers make in the line of duty. For that reason, police officers from Canada and the U.S. gather on Parliament Hill in Ottawa every September to remember the 330 police and peace officers killed in Canada since Confederation. “I don’t think we should forget these things,” Sinclair said.

Hoare’s own sacrifice remained all but forgotten until a few years ago. He retired from the police department almost two years to the day after the shooting, and went to work in the security department of B.C. Electric. He was never the same physically after the shooting, and he sometimes woke at night screaming and replaying the scenes in his head, wondering how it might have turned out differently. He was 85 before he received a Chief Constable’s Commendation from the Vancouver Police Department for his courage in the line of fire. The commendation he received in 1992 hangs over his bed. “It’s kind of like a medal, you know?” Two years later, the Worker’s Compensation Board finally agreed that he had suffered post-traumatic stress disorder and awarded him $15,000.

Charles Boyes: police officer, husband, father, son.

Addendum

Later investigation implicated the anonymous caller as a known robbery suspect named “Fats” Robertson. The foursome usually robbed banks together but this time he was not invited. He was angry he was left out, and phoned the police on his friends. Consequently, there was already a policeman inside the bank when the other three suspects arrived.

More information

The shootout at False Creek Flats

by Eve Lazurus

Every Place Has a Story

Charles Boyes

Constable Oliver Ledingham

February 26, 1947, remains one of the darkest days in the history of the Vancouver Police Department, where two officers were killed and a third was injured.

Constables Oliver Ledingham and Charles Boyes were shot and killed by three bank robbery suspects, and Detective Percy Hoare was shot and wounded.

The following story is reprinted with permission of the Vancouver Sun newspaper, originally published on February 26, 1997, written by Lindsay Kines.

Percy Alan Hoare returned to the scene of the crime 50 years later and saw nothing he remembered. A Skytrain now skirted the railyard near Clark and Great Northern Way, a new Home Depot store sprawled next to the tracks and someone had even paved the side roads. The 90-year-old former police detective surveyed the site of one of the most horrific gun battles in Vancouver Police history and found nothing familiar. “It’s all changed,” he said. All except for the grass and brambles still choking the ditches near the tracks – Hoare remembered them too well. Fifty years ago today, the Vancouver Police detective fell there, two bullets in his leg and shoulder, two fellow officers dying nearby, and a would-be bank robber lying dead a few metres away. The shooting stunned a city just two years out of the Second World War, scarred a police department and, like so many murders before and since, wounded more people than were shot that sunny afternoon.

If anyone doubts the damage done by a few seconds of violence, the shooting on False Creek Flats might convince them otherwise. It left a senior police detective haunted by nightmares and a boy without his father.

It led to the death of a fourth man by capital punishment, forever altered the life of a six-year-old girl, and remains so painful for some family members that 50 years after that day, they still don’t want to talk about it. “People just don’t know what you go through,” Naomi Macey said in a telephone interview this week from her home in Calgary. Half a century ago, she lost her father in the gunfight. The memories of that day and its aftermath still catch in her throat. “It had,” she said a “horrendous impact on our family.”

The events of Wednesday, February 26, 1947, began routinely with an anonymous call to police headquarters just before noon. The caller told a detective that men were putting on masks in a car near First and Renfrew, apparently preparing to rob the Royal Bank. The detective dispatched plainclothes officers to the scene, and the sudden police attention apparently spooked the would-be robbers. They took off in a maroon car, which they later abandoned in front of a house at 2325 Kitchener. Hoare and his partner, George Kitson, found the car a short time later. While Kitson stayed with the stolen auto, Hoare went in search of the bandits. He soon spotted 12-year-old Arnold Montgomery near Lord Nelson School. The boy said he had seen the three men, and Hoare took him in the police cruiser to help hunt for the trio.

They headed west and saw the suspects walking along the railway tracks near the Great Northern Roundhouse. Arriving only minutes after officers Charles Boyes and George Ledingham, Hoare parked the car, showed Montgomery how to work the radio and ran to help. Hoare later testified that he saw Ledingham flash his badge and step in front of the three men – subsequently identified as Harry Medos, 23, Douglas Carter, 18, and William Henderson, 17. “They spread out in a line, coming toward me on the tracks,” Hoare testified. “And when I was about 10 feet away, I asked: ‘Who are you three fellows anyway?’” There was no reply. Then the wind blew open Henderson’s coat and Hoare spotted the butt of a handgun sticking out of his pants. The detective reached down, pulled out the gun and asked: “What are you doing with that?” Before he could say anything else, all hell broke loose.

Running along the tracks, Medos and Carter wheeled and fired on the officers, killing Boyes, 39, and Ledingham, 40, and wounding Hoare in the hip. “I tried to get my gun out as I fell,” Hoare said later. “As I did this, a bullet hit me in the left shoulder.” He lay quiet for five seconds, feigning death. Then, still prone and bleeding, he shot the running Carter and saw him fall in the weeds. Medos and Henderson headed in another direction and Hoare, who had learned to shoot on a farm in Alberta, fired a long, arching bullet that hit Medos in the buttocks. By then, Carter was back on his feet and Hoare, still on the ground, fired again. This time, Carter fell and did not get up. “I could hear him breathing from where I sat,” Hoare told a coroner’s jury. “He must have expired a short time later.”

Montgomery, who watched the shooting from the police car, radioed for help, then ran to Hoare’s side. Now retired from his job at B.C. Electric and living in Parksville, Montgomery, 62, said he has kept his role on that fateful day to himself. “I never told anybody, hardly,” he said. “Just a few close friends. I just didn’t want to talk about it, that’s all. It’s something that’s in the past and it’s not important anymore.”

Roy Tabbutt arrived at the scene a few moments after the shooting just as Boyes was closing his eyes. The two men were partners for two or three years until both got promoted to plainclothes duty earlier that year. The friends saw each other for the last time only minutes before the shooting. Tabbutt was headed in one direction searching for the suspects and Boyes in another, but for some reason, they swapped routes, Tabbut said. “The next time I saw him, he was dead.” Now 84 and long since retired from the police department, Tabbutt has often wondered over the years what might have happened if he and Boyes had not changed routes. He has never forgotten that day. “I guess it’s one of those things, you know, that happen when you work like that,” he said.

Police found Medos and Henderson holed up in a basement at 647 East Sixth, and seven months later, Medos was hanged for the murder of Boyes. Henderson was convicted, but acquitted on appeal. He subsequently served time for heroin possession, and his whereabouts today are not known.

Police estimated that 100,000 people stood 10-deep along Burrard and Georgia streets for the funeral of the two dead officers. Naomi Boyes, who was just six years old at the time, did not attend the funeral, perhaps because she was considered too young. She was not, however, too young to absorb the pain. “I remember being told and then everything kind of went blank.” Now a mother of two boys, Naomi Macey, 56, spent four years in therapy in later life to work through that time. “I kind of lived in my own little world, but I think I’m sort of coming out of that now,” she said. “Things are seeming to be a lot better, but it did take a long time.” She remembers her father performing magic tricks, which he had learned from the Fakirs in India, where he served in the British Army. She remembers, too, her father inviting other policemen over in the evening to play poker. She would sneak from her bed and creep up on to his knee to watch them all play. Fifty years after his death, certain events still trigger the emotions of that time. “I guess the only other thing I can say about it is every time a policeman dies on duty, it’s like an intense blow to the solar plexus for everyone in my family,” she said. “I went to a bank in Calgary close to where I work last spring and I arrived about 15 minutes after it had been robbed and my stomach did flip-flops just looking at the scene.” Her mother, who remarried, has said not a day goes by that she doesn’t remember that time. “It seems that these kind of intense incidents in life imprint themselves on us on a cellular level,” Naomi Macey said. “And so every time something comes up to remind us of this, all the emotions come right to the surface again.”

Bill Ledingham, who was 13 when his father died, prefers not to talk about that time now. A retired schoolteacher, he said he remembers little of it, except that he had to work summers after his father’s death to earn extra money. “I liked those days,” he said. “I learned a lot about life digging ditches.” But he sees no value in dredging up the unpleasant past – the anniversary stories only upset his mother and serve no real purpose.

Retired Vancouver Police Inspector Ian Sinclair – whose own father, Gordon, was killed on the job in 1955 – said he understands Ledingham’s reluctance. Sinclair said his own mother and sisters suffer every time something is written about their dad. He also said there is value in remembering the risks of the job and the sacrifices officers make in the line of duty. For that reason, police officers from Canada and the U.S. gather on Parliament Hill in Ottawa every September to remember the 330 police and peace officers killed in Canada since Confederation. “I don’t think we should forget these things,” Sinclair said.

Hoare’s own sacrifice remained all but forgotten until a few years ago. He retired from the police department almost two years to the day after the shooting, and went to work in the security department of B.C. Electric. He was never the same physically after the shooting, and he sometimes woke at night screaming and replaying the scenes in his head, wondering how it might have turned out differently. He was 85 before he received a Chief Constable’s Commendation from the Vancouver Police Department for his courage in the line of fire. The commendation he received in 1992 hangs over his bed. “It’s kind of like a medal, you know?” Two years later, the Worker’s Compensation Board finally agreed that he had suffered post-traumatic stress disorder and awarded him $15,000.

Oliver Ledingham: police officer, husband, father, son.

Addendum

Later investigation implicated the anonymous caller as a known robbery suspect named “Fats” Robertson. The foursome usually robbed banks together but this time he was not invited. He was angry at being left out, and phoned the police on his friends. Consequently, there was already a policeman inside the bank when the other three suspects arrived.

More information

The shootout at False Creek Flats

by Eve Lazurus

Every Place Has a Story

Oliver Ledingham

Constable Gordon Sinclair

On December 7, 1955, Constable Gordon Sinclair had just finished having dinner with his family at their home at 1600 W. 14th Avenue, when he headed back to his patrols of the southwest area of Vancouver. Fifteen minutes later he would be dead just a few blocks away.

Constable Sinclair was the first officer to arrive at 1500 W.3rd Avenue for a report of two suspicious men prowling in the lane. When his cover unit pulled up, they found his car door open, the engine running, and Constable Sinclair hanging halfway out of the vehicle. He had been shot once in the head and once in the back. His overcoat and tunic were still buttoned up, covering his revolver, indicating he had no warning or chance to defend himself.

When Constable Hugh Wiebe arrived, he saw the two suspects fleeing in a blue convertible, with a third suspect at the wheel. As he pursued the vehicle, he watched the first two suspects get out and flee on foot at W.5th Avenue and Fir Street. When officers searched the area of W.5th and Fir hours later, they found a loaded but unfired .45 calibre pistol, which had been thrown by the fleeing suspects. It was not, however, the murder weapon.

Constable Wiebe broadcast the information to his fellow officers, continuing the pursuit of the vehicle, but he lost it several blocks later.

The blue convertible was located three hours later, and Constable Devries immediately recognized it as belonging to a known bank robber by the name of Joe Gordon. Within several hours, Gordon was arrested while hiding out at a downtown rooming house on Howe Street near the Granville Street Bridge. Despite strong suspicion – and that he was known to have access to firearms and was out on bail on an armed bank robbery charge — there wasn’t enough evidence to hold him, and on December 12th he was released without charge.

A break in the case finally came two months later, in February of 1956, when the second suspect Donald Carey, was arrested in Toronto. As he was facing the death penalty, he quickly agreed to give evidence against Joe Gordon. He told investigators the circumstances of the murder and took them to the murder weapon, a .38 Webley revolver, which was hidden in an old stump near W.5th and Fir.

He told investigators that he and Gordon were casing a business in the lane for a future break-in to crack the safe. They were surprised to see Constable Sinclair and realized they were facing serious jail time if the guns they were carrying were found. When Constable Sinclair called them over to his police car, Joe Gordon saw a way out. They calmly walked up to the police car and briefly spoke to the constable, who was sitting in his car. As the constable placed his left hand on the door handle to open it and get out, his right hand reached for his radio microphone.

Joe Gordon pulled his gun and pointed it at the officer’s head. “If you touch that thing I’ll blow your head off,” he said, right before pulling the trigger, shooting him in the head. Constable Sinclair fell out the door and landed face down on the road. Joe Gordon then stood over him and shot him again in the back.

Both men were convicted and sentenced to hang. Joe Gordon was hanged on April 2, 1957, at Oakalla Prison. Donald Carey’s death sentence was later commuted to life in prison, where he remained until March 3, 1968, at which time he was paroled.

Gordon Sinclair was a world-renowned player of the Highland bagpipes, played in the Vancouver Police Pipe Band, and was president of the B.C. Pipers Association. He was a gifted and skilled musician, who also played the side, tenor, and bass drum. He shared his gift by teaching the bagpipes to whoever wanted to learn. His two daughters took up Highland dancing at an early age, but lost interest after his death. His one son, Ian Sinclair, became an accomplished piper as a result of his father’s teaching. He followed in his father’s footsteps, joining the Vancouver Police Department and playing the bagpipes in the Vancouver Police Pipe Band. He retired as an inspector after a long and highly successful career.

Constable Gordon Sinclair was 40 years old when he died, and had served 14 years with the Vancouver Police Department.

Gordon Sinclair: police officer, father, husband, son.

More information

VPD Pipe Band

Gordon Sinclair Memorial Fund

Gordon Sinclair

Detective Lawrence Short

It was February 9, 1962, when Vancouver Police Detective Larry Short of the Fraud Squad received a call from a clerk at a travel agency reporting a man trying to purchase airline tickets with a credit card believed to be stolen.

Detective Short set out with Constable Len Galbraith for the Bayshore Hotel, where the suspect was registered. The officers decided that since fraud suspects were rarely violent, Constable Galbraith would wait outside in their police car, just in case he tried to escape.

Assistant Hotel manager Larry Kingston accompanied Detective Short to the suspect’s hotel room in case the door needed to be unlocked. Eric Lifton opened the door when they knocked and they both entered the room.

Mr. Lifton was calm and cooperative as Detective Short interviewed him. Paul Egley, the travel agency clerk, came to the hotel room a short while later. As Mr. Egley was making a call to his office, he heard Detective Short shout that the suspect had a gun.

Lifton had pulled a hidden .25 calibre pistol from his waistband and pointed it at the three victims. Detective Short tried to persuade him to put the gun down and surrender, but to no avail.

“I could do this,” stated Lifton, as he pointed the gun first at his own temple, and then at Detective Short. “I have done worse things.” He ordered the three men to lay down on the floor.

Detective Short, fearing that he was about to be shot, reached for his .38 calibre service revolver, surprising Lifton, who yelled, “What are you doing?”

The detective shot first – from a prone position on the floor, less than six feet away – hitting Lifton in the stomach. His heavy coat, shirt button and belt buckle deflected the bullet and he was not injured. Before Detective Short could fire again, Lifton returned fire and emptied his gun into all three men still lying on the floor.

The room went silent as Detective Short and Larry Kingston both lay dying, and Egley lay wounded. Lifton grabbed Detective Short’s revolver and ran out of the hotel and into a taxi on Cardero Street.

Meanwhile, Constable Galbraith was still waiting outside with no idea what had just occurred. He recognized Lifton as he fled into the taxi, and flagged the car down. When he opened the door to speak to the suspect, Lifton said that Detective Short had already interviewed him and told him he could go. Galbraith was doubtful and told him to wait until he confirmed his story.

Lifton suddenly pulled out the hidden revolver and pointed it at Galbraith. He ordered him to get into the back of the taxi with him, and Galbraith had no choice but to comply. Lifton told the taxi driver to take them to the airport. As the taxi pulled ahead to leave, Lifton told Galbraith he was using Detective Short’s gun.

Detective Galbraith realized that his partner must be dead. When Lifton ordered him to hand over his revolver, he knew he had to act to prevent being shot himself. When he glanced down at the revolver pointed at him, he could see that the chambers of the cylinder were empty.

Galbraith quickly slapped the gun from Lifton’s hand, and after a short struggle was able to handcuff him. When he checked the gun later, he was relieved to discover he had been correct about the empty chambers.

Three months later, on May 10, 1962, Eric Lifton was convicted. He was sentenced to hang on July 31, 1962, but four days before his execution his sentence was reduced to life in prison by the Federal Justice Minister after consultation with the Prime Minister. Shortly after, the death sentence was abolished in Canada by an Act of Parliament.

After several years in Kingston Penitentiary, Lifton was transferred to prison in the United States, where he served the rest of his sentence. He obtained his law degree in prison and went on to work as a lawyer in the United States.

Larry Short: police officer, father, husband, son.

More information

Lawrence Short

Reserve Inspector Arthur “Stan” Trentham

It was September 16, 1963, and the BC Lions were playing an evening game against the Montreal Alouettes at Empire Stadium in Hastings Park. Vancouver Police Reserve Inspector Stan Trentham was directing traffic, which was common for Reserve VPD officers. There was heavy traffic and Trentham was stationed at Windermere and E. Hastings Street. He was standing in the middle of the intersection, as his training dictated, wearing his full uniform, an orange reflective vest, and holding a flashlight with a red lens.

It was a clear night, with good artificial lighting, and even though the traffic was heavy, it was slow-moving.

Just after 8:00, Trentham was suddenly struck by an eastbound vehicle. Estimated to be travelling at 35 mph, the vehicle carried him 80 feet before stopping. Witnesses reported seeing the vehicle, a late model car, stop further along east on Hastings. The driver got out and looked around, then got back in and drove away.

Reserve Inspector Trentham died at the scene. He was 49 years old.

The driver, accompanied by his lawyer, turned himself in at the Vancouver Police station at 475 Main Street the next day. He admitted to being the driver and was charged with hit-and-run.

Stan Trentham was the type of man who loved life, always had a smile on his face, and made the best of any situation. As a young man, he served as a Seaforth Highlander and was in the honour guard for the visit of Queen Elizabeth and King George VI in 1939. He worked as a tram conductor for BC Trams on the Vancouver to Marpole route, and as a toll collector on the Oak Street Bridge. He was a Reserve officer with the Vancouver Police Department for six years.

Stan Trentham: police officer, husband, father, son.

More information

Arthur “Stan” Trentham

Constable Larry Esau

On June 29, 1966, Constable Larry Esau was on patrol, riding his red 1965 Harley Davidson Vancouver Police motorcycle eastbound along East Hastings Street.

As he approached Woodland Drive, a vehicle suddenly pulled out into his lane. He was unable to stop in time and struck the vehicle. The constable was thrown 64 feet and suffered serious injuries. Tragically, he died six hours later at Vancouver General Hospital.

Constable Esau was 23 years old, and had just graduated from a Vancouver Police motorcycle training course a few months prior. His instructor described him as the best in his class.

A former RCMP officer, Constable Larry Esau served with the Vancouver Police Department for three years.

Larry Esau: police officer, husband, son.

More information

British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial

Larry Esau

Constable Paul Sanghera

It was 1:00 in the morning of January 8, 1982, when Constable Paul Sanghera and his partner were on patrol in East Vancouver. A recent snowfall had blanketed Vancouver’s roads, making them slippery and treacherous to drive.

The officers stopped to investigate an abandoned vehicle at the side of the road at E.57th Avenue and Argyle Street. They got out of their vehicle and Constable Sanghera opened the car’s door to look for the registration papers in the glovebox. As they stood beside the abandoned vehicle and discussed what to do, they decided Constable Sanghera would remain with the vehicle, while his partner returned to their squad car to call for a tow truck.

Suddenly, a pick-up truck came around the corner and lost control on the icy street, striking the abandoned vehicle and Constable Sanghera. The officer died immediately. He was only 22 years old, and had been a Vancouver Police officer for just over a year.

The driver was found not at fault and the collision was blamed on weather conditions.

Paul Sanghera grew up in Richmond and attended Richmond High School. He is remembered as a tenacious and keen athlete who enjoyed soccer and played on the Vancouver Police soccer team.

Every year in April, police officers and Vancouver high school students play in the Paul Sanghera Memorial Soccer Tournament, where they honour Constable Sanghera’s memory.

Paul Sanghera: police officer, son, brother.

In the fall of 2024, families and colleagues of fallen officers from across Canada shared their personal stories of loss in a documentary showcasing the annual Canadian Police and Peace Officers’ Memorial in Ottawa, including Paul Sanghera’s brother, Mike. Stream the video

More information

British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial

Paul Sanghera

Sergeant Larry Young

On February 2, 1987, the VPD’s Emergency Response Team was called on to assist the Drug Squad with a high-risk arrest. The highly-trained and heavily-armed team handled all such arrests involving the possibility of armed suspects.

Sergeant Larry Young was a team leader, and even though he was on annual leave, he joined the team for the arrest.

The warrant was for John Sheffield, a well-known high-level cocaine dealer, who was wanted for cocaine trafficking. He was also the suspect in the shooting of another man in a drug deal one month prior. The victim had been uncooperative and there had not been enough evidence to arrest Sheffield.

Just after 9:00 p.m., the seven-member team arrived at Sheffield’s address, the basement of 3416 W.2nd Avenue, and prepared to enter the suite. Members were trained to use the element of surprise – to enter a premise quickly and arrest the suspect before they would have time to respond. They had no way of knowing that in a state of drug-induced paranoia, Sheffield had obtained a police scanner. Even though it was defective and could not pick up police radio conversations, it would squelch loudly when a police radio microphone was keyed. He was waiting inside, armed with a .30 calibre M1 carbine rifle pointed at the door, ready to shoot the first police officer through the door.

That police officer was Sergeant Young, who was killed immediately by a gunshot to his head.

During the quick, intense gun battle that began immediately as they entered the suite, a second officer, Constable Al Cattley, was shot and wounded in the leg. Sheffield was fatally wounded.

During his 18-year career, Sergeant Young worked in many areas of the VPD. He was one of the founders of the Emergency Response Team, and helped write their training manual. He was a dedicated, highly decorated and highly trained officer, who had been recently promoted to sergeant. He had led his team in the dramatic rescue of a baby held hostage only one month earlier.

Larry revelled in the challenge and camaraderie of sports, and was in excellent physical condition. He enjoyed running and playing rugby, and was passionate about karate, an eager student who gave it his all. He continues to be an inspiration for team members.

Each year, on the last Sunday of May, the Larry Young Memorial Run is held to remember and celebrate the life of Sergeant Larry Young.

Larry Young: police officer, father, husband, son, brother, friend, partner.

More information

British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial

Fallen police officer honoured with park dedication

CBC News

June 7, 2009

Larry Young

The research and original writing of the profiles of the VPD’s fallen officers was done by now-retired VPD Sergeant Steve Gibson and Constable Tod Catchpole.

The Memorial project was made possible with the generous support of the Vancouver Police Foundation.

The Vancouver Police Museum provided the photographs and assisted with the research.

VPD Officer Ensures Headstones

Acknowledge Officers’ Ultimate Sacrifice

In September 2009, Vancouver Police Constable Bill Taylor drove by a small cemetery outside Ottawa and saw four police officers laying a wreath at a grave. He learned this was an annual event to honour members from their police force who had died in the line of duty.

When he returned home, Constable Taylor researched the final resting places for the 16 Vancouver Police officers who have been killed in the line of duty, and discovered that some were buried in long-forgotten locations. Over the next two years, he made it his mission to find out where those unknown final resting places were.

Once the gravesites were located, Constable Taylor visited each one, and noticed that none of the headstones acknowledged the ultimate sacrifice of the fallen officers. He sought funding for additional grave markers, with approval from family members, and thanks to a grant from the Vancouver Police Foundation, he was able to purchase the headstones, giving the officers the honour they were due.

We will never forget.